December 17th 2021 in Cundill history hub

From the Reviewer’s Desk

2021 Cundill History Prize winner Marjoleine Kars, Professor of History at University of Maryland, Baltimore County, on what can happen when readers and historians encounter each other in the Books pages.

For several years now, I have been a regular contributor to the Washington Post’s Books section. At first, I was assigned new non-fiction in my field—early American history—but now, I have the latitude to occasionally suggest a book I would like to review. Given that women authors are under-reviewed in newspapers generally, I love to showcase the work of female scholars, particularly books focused on gender and race.

Bringing other scholars’ work to light in a newspaper with a broad reach like the Post is one of the great payoffs of being a historian. I keep an eye out for new research that piques my interest, dive in, and then share: the struggles of a fallen Japanese woman in Shogunate Edo (Amy Stanley, Stranger in the Shogun’s City); the 1768 Boston Massacre reconceived as a family brawl (Serena Zabin, The Boston Massacre: A Family History; the story of an enslaved girl sold away from her mother, as recorded only on an embroidered feed sack (Tiya Miles, All That She Carried).

Newspaper reviewing is entirely different from writing about books for professional history journals, where the aim is to evaluate the use of evidence, the argument, and the ways in which the book advances scholarly debates or fails to do so. Instead, my goal here is less to critique (though some judicious assessment is helpful) but rather to provide readers with an interesting historical nugget, a bit of intellectual excitement that they might mull over for the rest of the day. I want to encourage readers to reconsider something they thought they knew. I also, ideally, want to make them think about how historians practice their craft, so they will be better able to assess historical non-fiction for themselves. If readers want to buy the book, so much the better. But given that most probably won’t, I want to provide an account that can stand on its own.

Most importantly I hope my mini-history lesson gives readers context for the challenging world around them. At the same time, I want to be an advocate for the historical profession. In the current moment of skepticism about the academy, and about truth more generally, I want to show the public just what marvelous, evidence-based, and usable scholarship historians are producing.

Not all works of history lend themselves to being reviewed in newspapers. There is a place in the academy for deeply researched but narrowly conceived monographs that advance specialized knowledge for professional audiences. Yet newspaper editors tend to be interested in expansive books that have broad appeal, are accessibly written, and spark conversation. I wish more of my colleagues would focus on making their work accessible to a larger public. Doing so does not mean sacrificing depth for breadth. But it does mean explaining specialized terms, using more vivid language, and providing concrete details. Above all, it requires articulating what is relevant in one’s work for living in today’s world.

It matters, for readers and historians to encounter each other, if only briefly, in the pages of a newspaper’s “Books” section. Historians are forever asking new questions, turning up unexamined sources, or interpreting old evidence in fresh ways. I hope that readers find relevance in this new work for understanding both public life and their own histories.

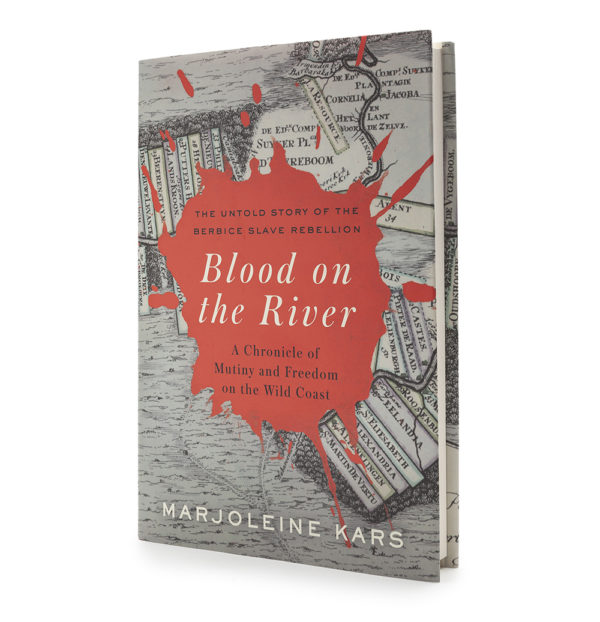

Marjoleine Kars won the 2021 Cundill History Prize for Blood on the River: A Chronicle of Mutiny and Freedom on the Wild Coast (The New Press). A noted historian of slavery, she is a professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and the author of Breaking Loose Together. She lives in Washington, DC.

Photo: Jasmine Nelson for the Cundill History Prize

Discover the 2021 Finalists | Re-watch our 2021 events programme | Find our more about the Cundill History Prize

Share this

Archive

2023: September (2) October (2)2022: April (1) August (3) December (2)

2021: August (1) September (1) December (3)

2020: August (1) October (2) November (2)

2019: September (3) November (2)

Recent Hub Contributions

Partnership Focus: Literary Review of Canada

Partnership Focus: Bookshop.org

Partnership Focus: HistoryExtra

15th Anniversary Special: Alan Taylor

15th Anniversary Special: Mark Gilbert

15th Anniversary Special: Peter Frankopan

15th Anniversary Special: Camilla Townsend